Riding Circuit

or Establishing the federal courts

Last time, I wrote that the second Trump Administration's expansive vision of executive power seems to encompass not merely a unitary executive but a unitary government, in which the President of the United States doesn't just take care that the the law be faithfully executed, but also decides what the laws are and adjudicates what they mean. It's interesting to note, however, that prior to the adoption of the Constitution, the federal government was in fact unitary, but it was Congress and not the President that held all the cards. Under the Articles of Confederation, there were no federal courts and no chief executive. Congress was the only organ of the federal government.

Counterintuitively, the Confederation Congress's legislative powers were minimal. It could not tax nor enforce its edicts domestically. Instead, as Akhil Amar describes, the Confederation Congress "acted less as a legislature than as an executive council, conducting foreign affairs and weilding many powers that the Crown had exercised in the old empire."

Since there were no federal "laws" at that time, there was no need for federal courts to interpret them. But Congress, as an executive council coordinating the fledgling states' collective foreign policy, did have an interest in certain litigation percolating through state courts that implicated international affairs and the conduct of war: prize cases.

I have previously written about the taking of “prizes” on the high seas during war. Prior to the advent of submarines, the primary danger to merchant shipping wartime was privateers, state-sanctioned pirates licensed to capture civilian vessels flying the flag of an enemy nation or even just on their way to an enemy port of call.

During the Revolutionary War, "[p]rivateers, sometimes with the authorization of Congress but often not, sought to intercept commercial vessels in the North Atlantic and claim them as prizes of war," writes G. Edward White. Once an American privateer brought his captured vessel to an American port, he could have it legally adjudicated as a prize and then auctioned for the proceeds.

In the Confederation period, prize cases were adjudicated in state courts. But state courts had an obvious bias towards America privateers over foreign merchants. Stacked prize adjudications had broad international implications, especially because the ships in question were not limited to English flag vessels. State courts were neither inclined nor well situated to take into account the foreign policy impacts of their decisions. Such cases "threatened to become a diplomatic embarrassment at a time when the United States was cultivating allies against Great Britain."

Luckily, Congress was given appellate jurisdiction over prize cases by the Articles of Confederation. In 1780, Congress established a 3 judge court to hear appeals from state courts in prize cases. But the federal prize court was hamstrung right from the jump because it had no power to compel states to comply with its decisions. At the same time, the prize court was not institutionally independent from Congress, which could influence its decision-making.

As a result, "[t]he first federal court was ... hardly an example of an active, powerful, or independent institution." But the experience with the prize cases convinced some among the Founders of the need for a robust and independent judiciary that could step in to adjudicate matters of federal concern that individual state courts were incompetent to handle.

Article III

During the Confederation period, "no expansive conception of a government with power in separate branches that served to check and balance one another existed in American jurisprudence." Rather, "[t]hat conception was invented in the Constitution itself."

In particular, the notion of an independent judiciary was rudimentary at best. In the pre-Revolutionary period, the "colonists had not usually regarded the judiciary as an independent entity or even a separate branch of government'" writes Gordon Wood. They had been of the opinion that there were "no more than two powers in any government, viz. the power to make laws, and the power to execute them; for the judicial power [was] only a branch of the executive, the chief of every country being the first magistrate."

In the Confederation period, on the other hand, it was legislatures that were understood to pull the judiciary's strings. In those years, Americans placed their confidence in state legislatures and were extremely wary of the other two branches.

Those attitudes derived from the colonial experience, when royal governors and judicial magistrates had oppressed the colonists on behalf of their imperial masters, whereas colonial assemblies were the the bulwarks of liberty and the fonts Revolution. As a consequence, both governors and courts were left anemic by early state constitutions, while legislatures held all the cards. Early state constitutions killed two birds with one stone by eliminating the traditional authority of governors to appoint and fire judges and granting it to the legislature.

But the experience of capricious states flouting Congress in derogation of the nation's foreign policy interests convinced the Framers of the need for a more robust federal judiciary that could overrule the states. The only question was whether there should be lower federal courts in addition to the supreme court.

Although some thought that the work of inferior federal tribunals could be performed by existing state trial courts, others worried that in a large federal republic of states, out-of-staters would get home-towned litigating in state forums. Consequently, a "tier of lower federal courts was necessary to afford out-of-state litigants and others who might not fare well in state courts with an alternative forum for resolving their disputes."

The Constitution ultimately vested Article III's judicial power in "one supreme court, and in such inferior courts as Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." Thus the prime law was a little coy on the question.

Most commentators have interpreted this provision to render the existence of lower federal courts entirely within the discretion of Congress. Amar, for example, says that the "Constitution did not require Congress to create inferior federal courts." Nevertheless, White argues that a "majority of the delegates to the Philadelphia convention seem[ed] to have endorsed the position that lower federal courts were mandatory, although Congress could decide when to create them."

As we have seen, Article III reserves a small number of cases for the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, but it also enumerates a wider set of cases falling within the ambit of the federal judiciary, over which SCOTUS holds appellate jurisdiction. The inferior federal courts (if they exist at all) exercise original jurisdiction over that wider world of Article III cases and controversies, along side state courts. Professor White counts four categories of federal jurisdiction:

Cases involving federal law (the Constitution, statutes, treaties, and in the modern era, federal regulations) or in which the United States is a party.

Cases touching on diplomacy and foreign affairs because they involve citizens, officials, or representatives of foreign nations.

Cases involving "navigable waters" (meaning those not under the exclusive control of any one state).

Cases in which an out-of-stater would get home-towned in state court (such as a litigant who claims ownership of land under foreign title).

Article III's enumeration of federal judicial jurisdiction makes clear that that the original purpose of the federal courts was to provide an alternative forum in cases where the parochialism of state tribunals threatened federal (i.e. interstate or international) interests.

Professor Amar writes that the Constitution empowered the federal judiciary to "vindicate national values against obstreperous States." The power of federal courts to unilaterally invalidate the actions of the other two co-equal branches of the federal government was, on the other hand, not so clearly anticipated, as I have written.

The Judiciary Act of 1789

In the Judiciary Act of 1789, the First Congress took up the task of establishing the federal judiciary. The first Supreme Court was composed of a chief Justice and five associate justices, who sat annually in two sessions. Congress also established lower federal courts. The Act "reflected the First Congress's conviction that lower federal courts were necessary, but at the same time its belief that Congress itself should fix ... the precise sets of cases appropriate for adjudication by lower federal courts."

The Judiciary Act established thirteen federal judicial districts, roughly approximating state boundaries, each with a single district judge. The district courts had jurisdiction over petty crimes, tax collection, and admiralty.

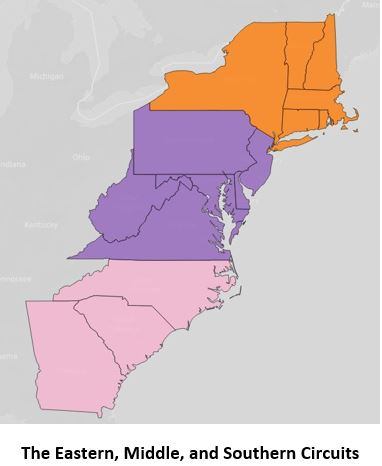

In addition, the Act established circuit courts, which were "a unique institution, whose composition and jurisdiction did not resemble any prior court in England or America." Initially, there were three circuit: eastern, middle, and southern. Circuit courts were composed of two Supreme Court justices and one of the district judges residing in the circuit.

Circuit courts could hear appeals from district courts in certain cases, and also exercised original jurisdiction in other cases. In addition to hearing appeals from district court in admiralty cases, they were courts of first resort for cases in which the United States, a foreign state, or a citizen of a foreign state was a party. Cases involving "diverse" citizens could also be brought in the district courts. Thus, Gordon Wood observes, "out-of-state litgants were able to remove their cases from what were often seen as the prejudiced state courts to the more neutral federal courts."

There was no automatic right of appeal from circuit courts to the Supreme Court. Instead, a "petition of error" was available only in cases where the amount in controversy exceeded $2000. On the other hand, appeals from state courts did not have a similar amount-in-controversy limitation.

Professor White speculates that the difficulty getting lower federal court decisions up to the high court when compared to state courts indicates that Congress "anticipated that the [Supreme] Court's primary role might be policing the boundaries of state and federal power, as opposed to developing a common-law jurisprudence in the federal courts."

Because of the requirement that Supreme Court justices "ride circuit" by attending regional circuit courts throughout the country when the high court was not in session, the "job description of a Supreme Court justice created by the Judiciary Act of 1789 was onerous in the extreme." The justices did not much like riding circuit and the first chief Justice, John Jay, argued that it was unconstitutional.

But the requirement forced the justices to leave their ivory tower in the federal city and journey around the country, hearing run of the mill cases and coming face to face with the real concerns of average people. In any event, Congress did not abolish the practice until 1869.

Given all that traveling, the "Supreme Court initially was not expected to do much," observes Wood. The high court heard only 87 cases prior to 1801. In addition to low activity, the early Supreme Court suffered from high turn over. According to White, in the first twelve years of its existence, twelve justices served on the court and only one for longer than 10 years.

In addition to the rigors of circuit riding, the supreme court's lack of reputation or clout made it an unappealing career prospect for ambitious up and comers. The court had lacked necessary "energy, weight and dignity," nor did it enjoy public confidence, Jay complained.

It was John Marshall that set the Supreme Court on the path from backwater to powerhouse. As we have seen, he had been appointed by a lame duck John Adams just as his party, the Federalists, had suffered a terminal shellacking in the election of 1789.

The judiciary was the last redoubt of the beleaguered Federalists and Marshall was determined to make the most his exile to the least dangerous branch. "More than any other single judge," Wood writes, "Marshall helped to carve out an exclusive sphere of activity for the judiciary that was separate from politics and popular legislative power."

One of his major reforms was to end the justices's habit of issuing seritum opinions (meaning that each justice wrote his own opinion explaining his specific views of the case), a practice customary in both English and American courts in the eighteenth century. Instead, the court began issuing a single "opinion of the court," nearly always authored by Marshall himself.

On the one hand, Marshall's unitary opinions enhanced the court's rhetorical potency by allowing it to speak clearly with a single voice. But since there was not yet a strong practice of justices appending concurrences or dissents to the majority opinion, the other justices were forced into "silent acquiescence."

As the same time, congressional reform of the court's appellate procedure in 1802 created the "certificate of division" procedure, effectively giving the court greater control over its docket and allowing it to expand its caseload. Among other tweaks, this system altered the composition of the circuit courts, so that each court was made up of a designated Supreme Court justice and a local district judge.

When they disagreed as to the correct outcome of a case, the two judges would certify their "division" to the Supreme Court.1 Very quickly, circuit court judges began to certify divisions by agreement, even in the absence of an actual dispute between them. As a result, White observes, "a Supreme Court justice with a particular interest in getting a question of law raised in a circuit case before the Court had an easy opportunity to do so."

Marshall's greatest legacy, though, was "maintaining the Court's existence and asserting its independence in a hostile Republican climate," Wood argues. As I have described, Marshall's pièce de résistance in this regard was his epic decision in Marbury v. Madison, in which he simultaneously established the court's power of judicial review and robbed his nemesis President Jefferson of the opportunity to do a damn thing about it.

By treating the Constitution as a kind of super-statute that could be interpreted and applied by federal courts, he carved out a special role for judges in the constitutional system and reserved to the judiciary a narrow but unassailable trump card: the power to declare the acts of the other branches unconstitutional and thus void.

The certificate of division procedure would be totally verboten under modern canons of judicial ethics, because the “practice not only permitted justices to ‘carry’ cases up to the Court but assumed that when the cases arrived, those justices would particulate in the Court’s resolution of the certified question.” Today, its well accepted that a judge may not participate in resolving an appeal of a case he or she decided in a lower court.