Judicial Review

In which John Marshall is caught up in a shady real estate deal

In the years of the early Republic, the judiciary was considered the “least dangerous,” as Alexander Hamilton said, of the three branches of the new federal government. Least dangerous because it was least powerful. Not only was the judiciary third among equals, listed last of the three branches in the Constitution, but it had no actual force or mechanism to compel compliance with its dictates. President Andrew Jackson apocryphally put his finger on the judiciary’s dilemma when he supposedly suggested of the Chief Justice’s ruling in favor of the Cherokee Nation in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), that “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.”

Over the ensuing two and a half centuries, however, the power and influence of the federal judiciary, and of the Supreme Court atop it, has steadily grown. Today, federal judges are without a doubt the most powerful and untouchable governmental officials in the nation, short of only the President himself.1

Akhil Amar points to a couple of factors that have contributed to the institutional rise of the federal courts over the course of American history. First, he notes that the the breadth, scope, and amount of federal laws themselves has ballooned, resulting in a concomitant expansion by Congress of the number of lower federal courts to hear cases and controversies arising under those ever-expanding laws. The other two politically accountable branches have been only too happy, meanwhile, to throw the hard questions to judges enjoying life tenure, allowing the courts to play an increasingly central role in the resolution of the pressing political and social disputes of the day (although they simultaneously claim not to answer so-called “political questions”).

In the early twentieth century, Congress enacted judicial reforms laws that gave the Supreme Court “near-plenary authority to define its own agenda, a luxury once possessed only by the political branches.” Thus, “even as the third branch has risen vis-a-vis the first two, so has the Supreme Court risen vis-a-vis the lower federal bench.” Today, some commentators argue that the court’s discretion is so wide that it is not a court at all. Rather it is a kind of unaccountable super-legislature that can nullify without consequence the laws of the nominal, democratically-elected legislature.

The jewel in the crown of judicial supremacy is surely the power of judicial review, because it is this doctrine that allows the courts to nullify the actions of any other unit of government, state or federal, that they declare to be in conflict with the Constitution. Yet, the awesome power of judicial review arises from the fairly basic proposition that, in order to resolve a legal dispute, a court must harmonize the laws that apply to the case, and if it cannot apply them consistent with each other, decide which one governs.

The “idea that judges could declare laws void when contrary to the principles of reason and justice had taken root” as early as the seventeenth century in England, writes Professor G. Edward White. Nevertheless, because the “British had no written constitution, […] the idea seems to have had more rhetorical appeal than practical effect.” By the 1780s, some state court judges “gingerly and ambiguously began moving in isolated but important decisions to impose restraints on what … legislatures were enacting as law,” notes Gordon Wood. Still, such decisions were “not easily justified.”

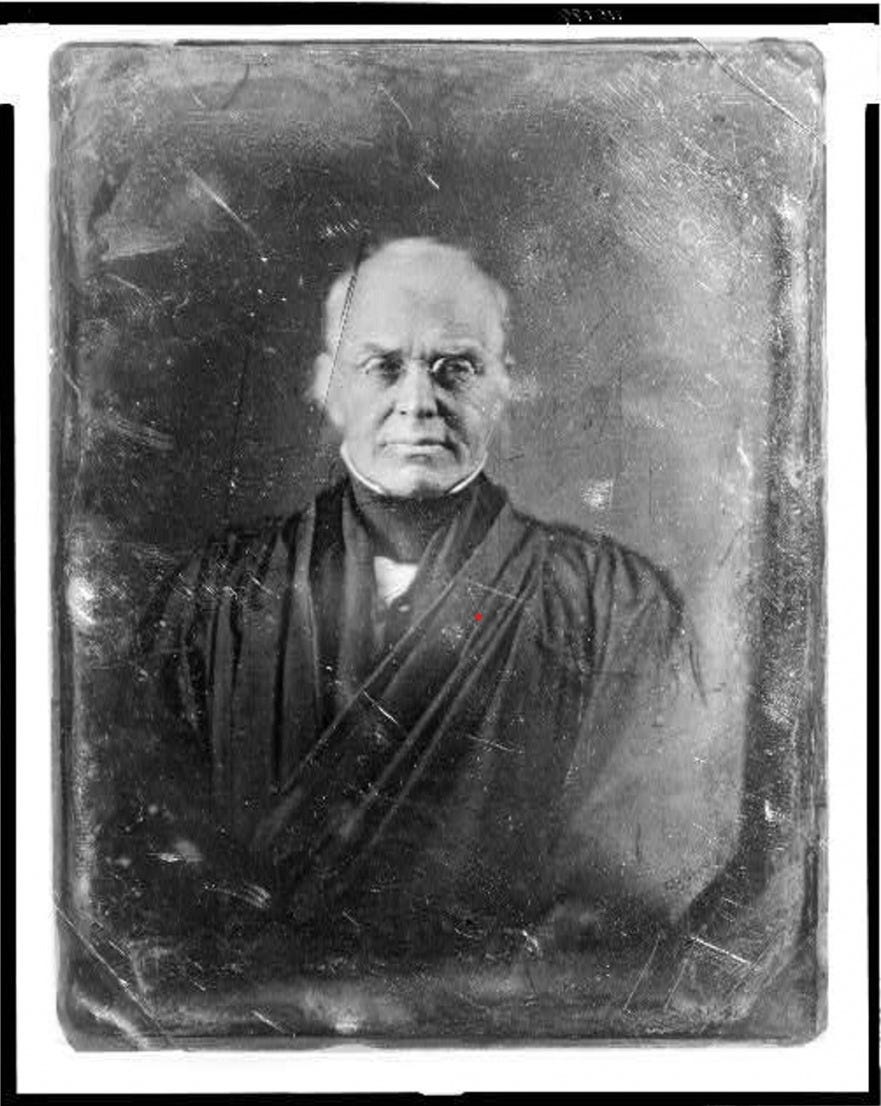

But it was really Alexander Hamilton who laid the groundwork for Chief Justice Marshall’s momentous decision in Marbury v. Madison (1803) establishing judicial review, when he wrote in Federalist # 78 that “the interpretation of laws is the proper and peculiar prerogative of courts” and that ”every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised is void.” Thus, “[n]o legislative act, … contrary to the Constitution, can be valid.” Chief Justice Marshall unabashadley channelled Federalist # 78 when he wrote in Marbury that “[I]t is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is.”

Vertical Review

Article VI, sec. 2 of the Constitution, known as the Supremacy Clause, provides that

[t]his Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

This provision makes federal law supreme over state law, in the case of a conflict between the two. Because the states are distinct sovereigns and not merely political subdivisions of the federal government, the feds cannot “commandeer” the states (i.e. take them over or command them to enforce federal law) nor force them to enact legislation mirroring federal law. But the Supremacy Clause resolves any conflict between differing state and federal laws ex ante in favor of federal law.

In Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816), the Supreme Court utilized its appellate jurisdiction, granted by section 25 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, over decisions of the highest state courts involving federal questions, to overrule the Supreme Court of Virginia and declare a Virginia law unconstitutional on the basis of the Supremacy Clause.

Martin was a British subject who was the nephew of the late Lord Fairfax. Fairfax had been a resident of Virginia during the colonial years and died during the Revolutionary War, leaving to Martin (who lived back in Britain) a large tract of land in what became the Commonwealth of Virginia in the meantime. In order to punish loyalists, the legislature of Virginia enacted legislation allowing the state government to confiscate their property and give it to citizens of the newly minted Commonwealth. Virginia did exactly that with Martin’s inheritance, granting it instead to Hunter.

There was only one problem, or rather, two: the Treaty of Paris (1783) and the Jay Treaty (1795). The Treaty of Paris was the peace agreement that ended the Revolutionary War. The Jay Treaty was a follow-on accord with Great Britain negotiated by Chief Justice John Jay that resolved lingering issues from the Revolution and ameliorated bad blood between America and the mother country which had accrued during years of turmoil resulting from the French Revolution (discussed briefly last time).

In these treaties, the United States committed to curb some of the worst excesses of the several states, many of which passed punitive laws in the bitter wake of the war that, like Virginia’s, targeted unrepentant loyalists. Virginia’s expropriation of Martin’s inheritance was a blatant and unapologetic violation of these treaties.

In the ensuing litigation in Virginia state court, the state took the position that not only was it’s confiscation not superceded by the contrary federal treaty but that the Judiciary Act of 1789’s grant of Supreme Court appellate jurisdiction over decisions of state courts was itself unconstitutional because it violated state sovereignty. Virginia’s highest court agreed. The U.S. Supreme Court, not so much.

On appeal from the Virginia Supreme Court, the inimitable Justice Joseph Story wrote the opinion of the Court,2 holding that the the U.S. Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction over state courts on questions of federal law was mandated by Article III of the Constitution. And since treaties trump contrary state laws under the plain terms of the Supremacy Clause, Virginia’s action was unconstitutional and therefore void.

Invalidating Virginia’s action, Justice Story also repudiated its argument that, the Supremacy Clause notwithstanding, state sovereignty was inviolable by contrary federal law. He pointed out that the Constitution was not merely some compact of convenience that could be disregarded by the states at their whim. It had been adopted by the ultimate sovereign, the American people themselves. Although the states were independent, they were nonetheless subordinate to the national Constitution to the extent of its reach, and it was necessary that the Supreme Court be able to void contrary state laws and judicial decisions in order to maintain the Constitution’s supremacy.

In Hunter’s Lessee, Justice Story took the Virginia high court to school:

The constitution of the United States was ordained and established, not by the states in their sovereign capacities, but emphatically, as the preamble of the constitution declares, by 'the people of the United States.' There can be no doubt that it was competent to the people to invest the general government with all the powers which they might deem proper and necessary; to extend or restrain these powers according to their own good pleasure, and to give them a paramount and supreme authority. As little doubt can there be, that the people had a right to prohibit to the states the exercise of any powers which were, in their judgment, incompatible with the objects of the general compact; to make the powers of the state governments, in given cases, subordinate to those of the nation, or to reserve to themselves those sovereign authorities which they might not choose to delegate to either.

Horizontal Review

Although neither states nor their courts were particularly excited to hear it, judicial review of state laws and the decisions of state courts seems to be obviously contemplated by the Supremacy Clause, which after all specifically name-checks state court judges and binds them to follow federal law, their own laws and constitutions notwithstanding. That, plus Article III’s grant of judicial power to the federal courts to decide cases and controversies implicating federal questions fairly obviously gives them authority to curb wayward state courts.

But where in the Constitution do federal courts derive their asserted authority to overrule the actions of the other coequal branches of the federal government? That authority may also derive in part from the Supremacy Clause. Professor Amar identifies in that provision a “ranking of laws reflect[ing] a democratic gradient.” The Supremacy Clause places the Constitution itself first “because it derived more directly and emphatically from the highest lawmaker: the entire American people.”

Next come federal laws “which shall be made in Pursuance” of the Constitution and treaties “made, under the Authority of the United States.” After that are state constitutions, and last (and definitely least), state laws. Federal laws (enacted by Congress) are thus only supreme to the extent that they are made in pursuance of the Constitution and treaties (negotiated and adopted by the President, with Senate confirmation) only to the extent they made under the authority of the United States (i.e. the Constitution).3 So if the judiciary decides what the Constitution means, it decides whether the actions of the other two branches are done “in pursuance of” and under the “authority of” that prime law.

And that brings us back to Marbury. In one sense, when Marshall said that it is emphatically the province of the courts to say what the law is, he was stating the trivially obvious. In applying the law to a case, courts have to figure out which rules apply and which don’t. But in the newly-established written constitutional order, this seemingly banal function took on new potency, one which state courts interpreting their own written constitutions had only just begun to appreciate.

Gordon Wood writes that the “first and most conspicuous source of something as significant and forbidding as judicial review lay in the idea of fundamental law and its embodiment in a written Constitution.” The common law which our courts inherited from England had evolved under a regime in which the “constitution” was a set of unwritten historical precedents and Parliament was the final authority.4 But the American system was and is profoundly different because our Constitution is a written document that derives its legitimacy directly from a different ultimate sovereign, the people.

Consequently, unlike the courts of England, the federal judiciary can fall back on a higher authority than the laws enacted by the legislature. They have done so by “legalizing” the political settlement that our republican government embodies, reading its founding instrument as a kind of super-statute that can be litigated and adjudicated by courts, but that Congress cannot unilaterally amend and the President is bound to faithfully execute.

But even if some of those of the Founding generation recognized the idea of judicial review, they would not have countenanced the modern practice of judicial supremacy, under which the U.S. Supreme Court has the final say in nearly all questions of federal law. “Missing in this conception of judicial power to declare laws void,” writes Professor White, “was any consensus that the power was exclusive in the judiciary, in the sense of precluding other branches from interpreting sources of law, including the Constitution.” Rather, the “Court was merely one constitutional interpreter, among a group of interpreters, operating within its own sphere.”

Amar argues that in fact, the original Constitution contemplated a “rather modest judicial role,” directed mainly at “enforcing federal statutes and ensuring state compliance with federal norms” and not pushing around its sister federal branches. Early practice reflects Amar’s contention. From the ratification of the Constitution up to Dred Scott, the court invalidated over thirty state statutes but only struck down a single federal law, the one at issue in Marbury.

So while it was understood that “courts would have the right and even the duty to refuse to enforce congressional statutes that plainly violated the higher law of the Constitution itself,” such cases would be limited to egregious and irreconcilable conflicts. In debatable cases, the courts would defer to the constitutional interpretations of the political branches. It was not the role of the court in the days of the early Republic, as it is today, for the courts to substitute their own preferred understanding of the Constitution for that of Congress or the President.

The most significant limitation on the power of the judiciary is Article III’s case or controversy requirement, which restricts the courts to only answering questions arising from specific and real disputes brought to them by litigants. Courts, unlike the legislature, are not at liberty to propound generally applicable rules of conduct for society as they wish. In fact, no court ruling is strictly speaking applicable to anybody who is not a party to the particular case in which the ruling is made.

But courts cannot treat every case as a tabla rasa and decide the questions presented in a vacuum, without regard to how other courts have treated those same issues. Such a system would be totally chaotic and unpredictable. Thus, as I have previously described, the doctrine of stare decisis requires courts to follow the precedents set in earlier court decisions. So in fact, when a court renders its ruling, the effect is much wider than the parties to the suit.

In recent years, however, the inferior federal courts have fashioned a more potent weapon to tame the executive than Chief Justice Marshall could have conceived in Marbury, the universal injunction. When the court issues this order, it directs the federal government to cease an action (or take one) requested by the plaintiff, not only as to the plaintiff themself but generally as to all persons wherever located in the jurisdiction. Thus, the court adjudicates the legal rights of those not before it.

In our era of lawfare, universal injunctions have been the bane of every presidency, Republican or Democratic, of the twenty first century. Seemingly any motivated interest group these days can stymie the most powerful individual on Earth by filing for a TRO in a favorable venue and obtaining a nationwide injunction against the executive.

Universal injunctions are highly controversial but have been rarely addressed by the Supreme Court because they occur mostly pretrial and generally only appear, if at all, on the court’s emergency or shadow docket. But such orders are often in reality dispositive of the case because the plaintiff can effectively kill a federal initiative by obtaining an injunction early in the case and then digging into protracted litigation.

Yet, universal injunctions arguably violate the case or controversy requirement by adjudicating rights of non-parties. In doing so, the courts step dangerously close to the line that distinguishes deciding cases from making laws. It will be interesting to see whether the recent controversies of the Trump Administration’s executive orders will finally prod the Supreme Court to address the practice of universal injunctions.

Who not only controls the military but apparently also can do crimes.

Chief Justice John Marshall was conflicted out of the case. Although he was not the eponymous lessee of the case’s famous style, he did claim an interest in a parcel of the Fairfax estate derived from the asserted title of Hunter.

The distinct terminology reflects the fact that many treaties had been made under the prior Articles of Confederation, and not technically the Constitution. The Supremacy Clause was intended bridge the gap and transform even those prior treaties into supreme federal law.

The King would beg to differ, naturally.