When Associate Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a judicial powerhouse who was also the preeminent conservative legal scholar of the modern era, passed away in February of 2016, then-President Obama had a once in a lifetime opportunity to upend the political valence of the high court for a generation by appointing a young liberal justice to fill the newly vacant seat. But Obama had one problem: the Republican-dominated Senate.

The Senate Republicans, led by Majority Leader McConnell, announced within hours of the news of Scalia’s passing that they would not confirm any candidate nominated by the president, and indeed would not even meet with or hold a hearing to consider anyone he nominated. Obama nevertheless proceeded reasonably by nominating on March 16, 2016 Merrick Garland, the politically moderate chief judge of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals who should have been palatable to the conservatives in the Senate.

But to no avail. The Senate stuck to its guns, asserting the novel proposition that since Obama was a lame duck, his successor should be given the opportunity to appoint Scalia’s replacement. In that way, the voters would be given a say in the matter through their selection of the next president.

Democrats complained that the Senate had a constitutional duty to provide advice and consent on the president’s judicial nominations. But legally speaking, the Republicans countered, the relevant constitutional provision governing Senate confirmation of judicial nominations functions not as a duty of the Senate to take action on the president’s nominees but rather as a limit on the president’s power of appointment.

They had a point. Art. II, sec. 2 of the Constitution provides that the president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint … Judges of the supreme Court … .” The text is clear that the president may not appoint Supreme Court Justices without the Senate’s advice and consent, but it does not put any affirmative obligation on the Senate to provide it. Article II definitely does not dictate any specific process, such as a hearing or vote on the president’s nominee.

So there was likely nothing legally objectionable about the Senate just flat out ignoring Obama’s nomination. But in announcing this new rule, the Senate was breaking with longstanding past practice. When the shoe had been on the other foot, Democrat-dominated senates had previously confirmed appointments by Republican presidents in 1988, with Anthony Kennedy, and in 1991, with Clarence Thomas.1 Long before that, a very different Republican Party had confirmed the appointment of Rufus Wheeler Peckham by Democrat Grover Cleveland in 1895.

Surveying the history of Supreme Court appointments over American history, scholars that analyzed the question at the time concluded that “the Senate has only refused to consider a President’s Supreme Court nominations in the highly unusual circumstance where the nominating President’s status as the most recently elected President has been in doubt.” Those circumstances have arisen when either the current president ascended to the office by succession rather than election or the next president has already been elected but had not yet taken office.

In the event, the Senate withheld a hearing on Garland, and when Donald Trump subsequently ascended the presidency, he nominated Neil Gorsuch for the same seat. The Senate Republican majority utilized the “nuclear option” of eliminating the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations in order to overcome the objections of Senate Democrats and confirm Gorsuch’s nomination on April 7, 2017.

Whatever the merits of the “Biden Rule,”2 as it was stupidly called, the rule itself was short lived. It was in fact dispatched by its own daddy, Mitch McConnell, only a few years later. In September 2020, the Notorious RBG finally succumbed to cancer, leaving a vacant seat available for appointment by President Trump. Now it was the Republicans who had an opportunity on the eve of a presidential election to secure the high court for decades to come.

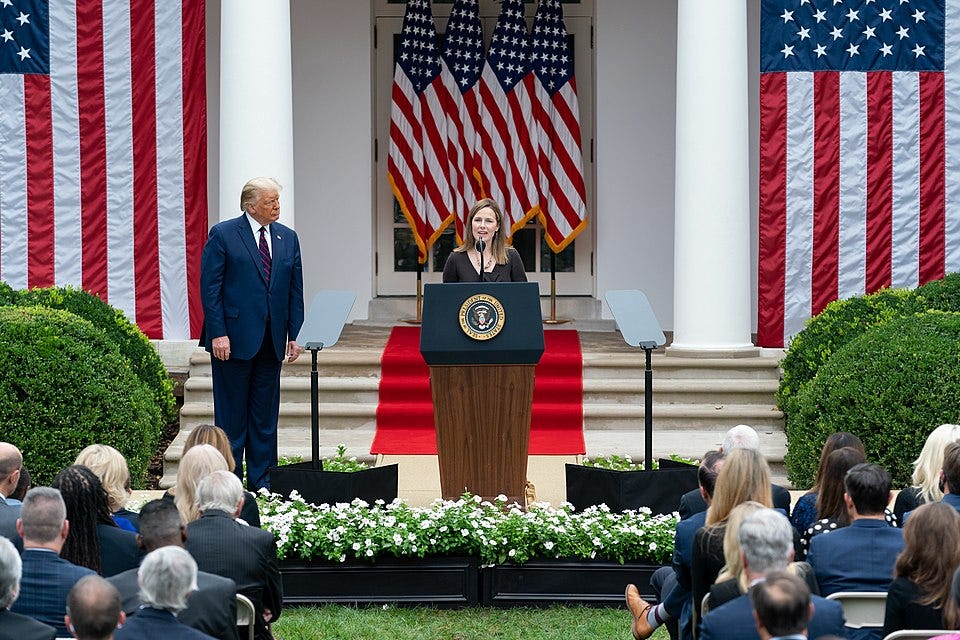

On September 26, 2020, Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett to fill the late Justice Ginsburg’s seat. McConnell’s recently announced rule would seemingly have dictated that the Senate should wait for the results of the upcoming presidential election before acting on Trump’s nomination. If Biden beat Trump in the 2020 election (as he in fact would do), he should have the opportunity to nominate his own candidate for Justice Ginsburg’s seat.

But of course, the crucial distinction from 2016 was that now the Senate and presidency were both controlled by the Republicans. In mercenary fashion, the Senate Republicans expedited Barrett’s hearing, confirming her appointment on October 26, 2020.

There was much lamentation and rending of blouses by the Democrats over the Republicans’ hypocrisy in jettisoning their own precedent so quickly and so brazenly. The whole episode reflected not the emergence of a new norm of Senate judicial confirmation so much as a cynical demonstration of the meta-norm of the Trump era, that norms are for chumps.

But self-dealing shenanigans with regard to judicial appointments is hardly unprecedented in American history. Indeed, the mother of all constitutional law cases, Marbury v. Madison (1803), arose out of appointment skullduggery carried on by some our most revered Founding Fathers, relating to commissioning of a group of Federalist judicial appointees who became known to history as the “midnight judges.”

Midnight in the district of good and evil

I have written how the vituperative and highly partisan presidential election of 1800, which pitted the incumbent Federalist Party of President John Adams against the Jeffersonian Republicans, represented of course by Vice President Thomas Jefferson, resulted in the “Revolution of 1800,” the “first major transfer of power in the life of the Federal Republic” according to Elkins and McKitrick. The previously dominant Federalist Party had alienated the voters with their odious and unconstitutional Alien and Sedition Acts. The Republicans swept to victory, ousting the Federalists from control of the presidency and Congress. Only the unelected judiciary remained in Federalist hands.

The Federalists were shocked and appalled by the results of the 1800 election. They “could not conceive the accession of Thomas Jefferson without sensations of horror.” Wild eyed anarchic Jacobins had somehow taken control of the federal government. The barbarians weren’t just at the gates, they had the deed to the house.

The Federalists clucked with disappointment like mother hens. What else should one expect from majority rule than the oh-so-predictable ascendency of a demagogue? But in reality, the Federalists were suffering from an existential crisis. “What the Federalists of 1800 could not now face, or even admit, was that the sovereign people had spoken for Jefferson, and not for them.”

The outgoing Federalists knew they had to retain control of their one remaining branch, the judiciary. The “election results only made the Federalists more desperate to hold on to the courts,” writes Gordon Wood. The Jeffersonian Republicans, meanwhile, “[w]ith good reason … had become convinced by 1800 that the national judiciary had become little more than an agent for the promotion of the Federalist cause.”

The rules in this era produced a prolonged lame duck session of Congress lasting until December 1801 that was still held by the Federalists (the new presidential administration meanwhile took office in March). In February 1801, while the results of the presidential election were still technically being contested in the House of Representatives, the Federalist Congress enacted a new judiciary reform law intended to further consolidate Federalist control of the federal courts.

The Judiciary Act of 1801, among other things, created a slew of new federal judgeships, including justices of the peace for the newly incorporated District of Columbia. The outgoing Federalist President Adams would have the opportunity to fill these judgeships before Jefferson could do anything about it.

The apocryphal legend has Adams hunched over his desk at 11:59 PM on the last night of his presidency frantically signing commissions for new Federalist justices as the clock ticked down to midnight. Although they signed the commissions just in the nick of time, the Adams Administration did not have a chance to get the commissions out the door and delivered to their intended recipients. That task was unfortunately left to Adams’s successor and frenemy for life, Thomas Jefferson.

When President Jefferson declined to acquiesce, the resulting confrontation teed up a judicial cage match between the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans, the stakes of which were the delineation of the separation of powers itself. The result was the greatest con law case of all time, Marbury v. Madison.

Yes, that Madison

In the real event, it seems, the commissions of the so-called midnight judges were all signed by 9 PM. But it was nevertheless true that, whether due to forgetfulness or lack of time, the commissions were not delivered prior to the expiration of the Adams presidency.

More interestingly, however, the commissions in question had been prepared by Adams’ Secretary of State, John Marshall, whose duty it also was to ensure that the commissions were timely delivered. Thus, the failure to perfect the commissions by delivering them to the new judges fell in Marshall’s lap. Although Marshall was still Secretary of State at the time, he had already been confirmed to replace Oliver Ellsworth as the new chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (he had yet to fill the position on the last day of the Adams Administration).

It also turns out that Marshall was Jefferson’s cousin, and they absolutely hated each other. According to Wood, the “enmity between the two cousins began during the Revolutionary War” during which, unlike Jefferson, Marshall “saw military action and suffered with Washington at Valley Forge.” Marshall’s military service had made a nationalist out of him and he remained a loyal Federalist. Jefferson on the other hand thought no Virginian worth a damn was a Federalist. Such a shame to see family quarrel over politics.

When Marbury, one of the midnight judges, brought suit against Marshall’s successor in the Jefferson Administration, James Madison, to compel the new secretary of state to deliver his commission, he was able to initiate the lawsuit directly in the Supreme Court by invoking a curious clause in the Judiciary Act of 1789. Thus it came to pass that the freshly installed Chief Justice Marshall would review a case, the central issue of which not only revolved around his own conduct but which arguably implicated his failure to adequately execute the duties of the secretary of state.

Democrats did refuse to confirm Reagan’s nomination of Robert Bork in 1987. But they gave him a hearing and a vote. Bork’s views on the law were legit wacky.

Then-Senator Biden had hypothetically suggested something similar in June of 1992 regarding President George H.W. Bush.