In Elk Grove United School District v. Newdow (2004), the U.S. Supreme Court denied a challenge to the inclusion of the phrase “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance recited every morning in Elk Grove’s public schools because the plaintiff lacked standing to challenge the state action in question.1 Justice Thomas, however, concurring in the judgment only,2 wrote separately to express his view that the entire project of incorporating the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause against the several states under the Fourteenth Amendment had been a misadventure from the outset. He opined that

[q]uite simply, the Establishment Clause is best understood as a federalism provision—it protects state establishments from federal interference but does not protect any individual right. These two features independently make incorporation of the Clause difficult to understand.

Because “States and only States were the direct beneficiaries” of the Establishment Clause, he argued, the “incorporation of this putative individual right leads to a peculiar outcome: It would prohibit precisely what the Establishment Clause was intended to protect—state establishments of religion.”

Perhaps it is indisputable, as many originalists like Justice Thomas contend, that the purpose of the Establishment Clause was at least in part to protect state establishments of religion from federal interference. But as I discussed last time, not everyone in late eighteenth century America was totally anamored of state interference in religious matters.

Controversy over state religious taxes (called “assessments”) to support religious education in Virginia led to the disestablishment of the Episcopal Church in that state with the enactment of Thomas Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786. Nor was Virginia alone. Sectarian disputation among religious sects in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries over who should hold the reins of power eventually resulted in the disestablishment of religion in every state in the Union before the mid nineteenth century.

Disestablishing my religion

As Bernard Bailyn writes, the “establishment of religion had been a problem for Americans from the first years of settlement.” I have observed that the aspriation of the early English colonists to obtain a society of pure religion in the New World worked at cross-purposes with their Protestant intuition that each individual was entitled to decide what that purity consisted of for themselves. The “very intensity of religious motivation and desire to specify and enforce a letter-perfect orthodoxy led to schismatic challenges to the establishment.” Indeed, in many colonies, the “sheer diversity of religious persuasions in the population made the establishment of any one church problematic.”

In the early years, the sparse and dispersed nature of settlement tended to tamp down on religious strife because religious dissenters could easily pick up and move on, as Roger Williams did when he founded the colony of Providence Plantations (known today as Rhode Island) after being expelled from Massachusetts for his nonconformist religious views.

Although disestablishment sentiment in the colonial era was generally “scattered and ineffective,” cantankerous religionists nevertheless objected to being required to pay taxes that supported a church to which they did not belong. They began to conceive of liberty of conscience as an inalienable right and some even advocated the complete separation of church and state.

This gripe about taxation took on revolutionary dimensions when a resurgent Parliament sought to enact assessments directly on colonists to support the Anglican Church. Indeed, fear that the imperial government would seek to establish the Church of England over all the colonies, wiping out the local options found in many colonies, stoked opposition to Parliament and the Crown in the mid 1700s.

But some revolutionaries later found themselves hoisted on their own petards when local dissenters deployed the same arguments against their own attempts to establish state religions after the Revolution. Patrick Henry had argued in Parson’s Cause that the “only use of an established church and clergy in society is to enforce obedience to civil sanctions” but later saw his own bill in the Virginia House of Burgess to assess taxes supporting religious education defeated by James Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, which asserted that “in matters of Religion, no man’s right is abridged by the institution of Civil Society and that Religion is wholly exempt from its cognizance.”

Gordon Wood cautions, however, that Madison and Jefferson misunderstood their victories in Virginia. “It was not,” he notes, “enlightenment rationalism that drove these evangelicals” to support disestablishment. It was rather “their growing realization that it was better to neutralize the state in matters of religion than run the risk of one of their religious opponents gaining control of the government.” He concludes that the “proliferation of competing evangelical religous groups coupled with the enlightmentment thinking of the gentry soon eroded what was left of the idea of a European-like coercive state church.” The last state to disestablish its church was Massechusetts in 1833.

That was not necessarily the end of state policing of religious matters because state common law, derived in nearly every case3 from the English common law, took for granted Christian orthodoxy. Thus, blasphemy remained a crime at common law, notwithstanding the disestablishment of religion. States also continued to enforce the Sabbath and dictated the terms under which churches could manage their own property under Pearson’s rule, from an 1813 English case.

Kurt Lash traces an evolution in the treatment of such religious laws and doctrines by state courts during the nineteenth century. By the end of the antebellum period, courts had either found secular justifications, as in the case of Sunday closure laws, or restricted the reach of religiously based doctrines to secular objectives, as in the case of the crime of blasphemy (which was limited to breaches of the peace). Still, there was no need to be coy about the fact that the secular day of rest happened to fall on the Sabbath; it was understood that religious motivations would continue to inspire public policy. Akhil Amar concludes that

[w]hat began as an agnostic but strict rule of federalism - no law intermeddling with religion in the states - was gradually mutating into a soft substantive rule: religion in general could be promoted, but not one sect at the expense of others.

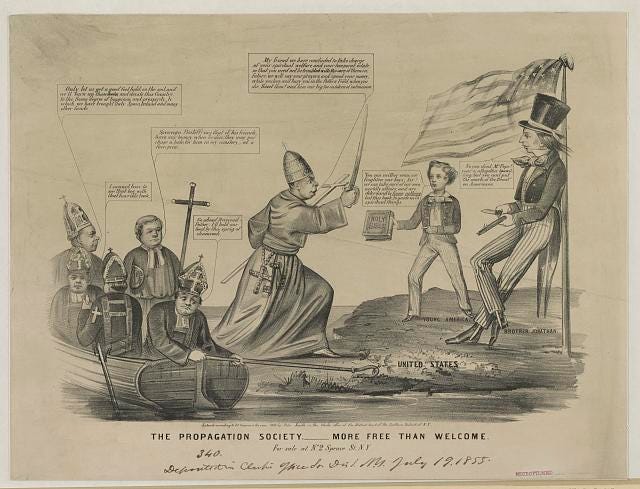

But the facile assumption that “religion” meant “Protestantism” became increasingly problematic as the nineteenth century wore on. The debate over separation of church and state morphed into a battle for public school funding in the North, waged between nativist Protestant “Know-Nothings”4 and the American Catholic Church, whose members were predominantly Irish and German immigrants.

Catholics resented paradoxically both the godlessness of public education and the reading in public schools of the King James Bible (to which they did not subscribe). The Catholic Church supported various initiatives to provide public funding for Catholic parochial schools, including direct financial support and tax relief for parents of attendees, as an alternative to the Protestant-dominated public schools.

Northern state legislatures responded, Lash recounts, with a “whirlwind of anti-Catholic legislation and constitutional amendments that prohibited ‘religious sects’ from receiving public school funds,“ which had the effect of freezing Catholic education out of public funding while solidifying Protestantism in public schools. The Know-Nothings seemingly did not perceive the double standard, or did not care that there was one. The “only way out of this impasse” Catholics realized by the 1860s was “to call for the removal of all religious instruction from the classroom.”

The Know-Nothings were an awkward but necessary ally of the new Republican Party at this time. The Republicans planned to coopt and absorb the Know-Nothings into their coalition, in order to concentrate on the real issues that mattered to them: secession and slavery. The final plank of the 1855 Republican platform, which opposed restrictions on “liberty of conscience and equality of rights among citizens,” was a “masterpiece of ambiguity” writes James McPherson.

Although the platform seemed to reject nativism, “by specifying ‘citizens’ it apparently did not preclude the Know-Nothing plan (which Repbulicans had no real intention of carrying out) to lengthen the waiting period for naturalization to twenty-one years.” The reference to “liberty of conscience” was also a “code phrase for Protestants who resented Catholic attempts to ban the reading of the King James Bible in public schools.”

The slavery establishment

A different struggle over the separation of church and state meanwhile was also waging in the South. In the early to mid nineteenth century, the Second Great Awakening stimulated an outburst of evangelical enthusiasm, concentrated especially in the North East, that “generated a host of moral and cultural reforms,” the “most most dynamic and divisive of [which] was abolitionism,” according to McPherson. The engine of abolitionism was evangelical Northern Protestantism.

Not only was slavery a violation of the God-given equal dignity of each human soul, Northern evangelicals argued, but the enslaved were not allowed to learn to read, which denied them the ability to directly experience the word of God. The right to access the word of God, by reading the bible on one’s own, was after all the original “protest” that had launched “Protestantism” in the first place. Southerners, desperate to prevent at all costs another slave uprising (such as that led by Reverand Nat Turner), were appalled at the very notion.

Southern slave owners declined to consider themselves the moral monsters that Northern abolitionists accused them of being. The result was a schism between Northern and Southern churches over the issue of slavery. Southern states regarded evangelical abolitionist agitation as a dire threat to the peculiar institution and any attack on the peculiar instittuion as an existential danger.

In response, Southern state legislatures “enacted a constellation of laws that strictly controlled religious exercise,” Lash says, to severely punish white abolitionists who, like the later Freedom Riders, went south to disrupt Southern white supremacy, and to strangle in the cradle the dangerous nascent power of grass roots religiosity in slave communities. In addition to heavily policing black religious assemblies and enacting draconinan punishments for distributing abolitionist literature like the Ten Commandments,5 slave governments directly regulated religious doctrine in the south, “licensing only proslavery ministers, dictating proslavery theology and doctrine, and generally suppressing—often violently—religious antislavery leadership (especially in black churches),” according to Frederick Mark Gedicks.

“By 1860,” Professor Lash concludes, “the South had erected the most comprehensive religious establishment to exist on American soil since Massachusetts Bay,” but not for the purpose of promoting piety. As in the case of speech, Southern states perverted and abused their traditional authority to establish religion, violating the rights of conscience of Americans, free and unfree, in order to maintain and perpetuate the slave power.

“So, what?” the originalist interrupts at this point. None of this tells us anything about the original public meaning of the Establishment Clause. Not only does most of the history described above post-date the enactment of the Bill of Rights, but debates over state level disestablishment are irrelevant to the meaning of the federal Constitution’s Establishment Clause.

But by the same token, the Establishment Clause, the original public meaning of which applied only to Congress, should have been equally irrelevant to the practices of the Elk Grove United School District, a political subdivision of the State of California. Yet every justice in Newdow, including the purported strict originalist Justice Thomas, assumed that the Bill of Rights would have been the relevant constitutional text to decide the case (had it not been dismissed on standing) even though the First Amendment is irrelevant to the question on its face.6

If the Bill of Rights, including the Establishment Clause, applies to local governments at all, that can’t be because of anything found in the original public meaning of the Bill itself. Rather, there must be another part of the Constitution that provides for such application. Originalists insist on looking in the wrong place for the original meaning of incorporation. Where in the Constitution should originalists be looking?

Enter the Fourteenth Amendment.

The court held that Newdow lacked sufficient legal custody of his minor daughter under California law to sustain a lawsuit on her behalf.

He thought there was standing but that Newdow should lose on the merits.

Except Louisiana, admitted to the Union in 1812, which to this day does not follow the common law, due to its French extraction. Much love to my alma mater, Tulane Law School!

The Know-Nothings organized themselves into secret fraternal societies. When asked about the proceedings of these secret societies, members would invariably respond, “I know nothing.”

Lash recounts that “[i]n 1850, Jesse McBride gave a young white girl a pamphlet on the Ten Commandments which suggested that slaveholders lived in violation of the Decalogue. McBride was convicted under a North Carolina statute making it a crime knowingly to circulate or publish any pamphlet with a tendency to cause insurrection or resistance in slaves.”

Justice Thomas would no doubt respond that he doesn’t think the Establishment Clause applies to states. But originally none of the First Amendment (or Bill of Rights more generally) was applicable to states. My point is that the answer to the question of whether or not states may establish religions under the federal Constitution cannot be found by examining the original public meaning of the Establishment Clause alone.