Last time I noted that, whilst the Revolution of 1800 repudiated the federal government’s attempt to punish subversive advocacy under the Sedition Act of 1798, states continued to police and punish officially disfavored views with the common law crime of seditious libel during the Antebellum Era. As with every other political issue in this period, the question of speech was sucked into the vortex of slavery.

The movement for abolition became increasingly organized and militant over the course of the nineteenth century, and abolitionists sought to communicate their arguments to the public through associations, rallies, meetings, and distribution of print media. Abolitionists even wrote southern slave owners directly, in an attempt to persuade them to abandon the peculiar institution.

Southern states responded by banning anti-slavery speech. Some states went so far as to criminalize the expression of any sentiments that could inspire dissatisfaction among slaves. Indeed, as Professor Werhan describes, Southern states were

not satisfied with halting the importation of antislavery advocacy. They demanded that Northern states outlaw abolitionist organizations and antislavery publications operating within their borders, and that Congress prohibit the mailing of antislavery publications to Southern destinations. Many Northerners violently disagreed with the abolitionists … [e]ven so, legislatures of Northern states resisted the call to suppress abolitionist advocacy at home.

Congress, however, expressly authorized (but did not require) federal postmasters to refuse to deliver abolitionist mailings in states that had outlawed them in the Post Office Act of 1836.

Repression by Southern states during the Antebellum Period was thus not limited to enslaved persons, nor to the Free Sppeech Clause. As Amar writes, the “structural imperatives of the peculiar institution led slave states to violate virtually every right and freedom declared in the Bill [of Rights] - not just the rights and freedoms of slaves, but of free men and women.” The North was not amused when Southern states, otherwise virulent proponents of states’ rights, attempted to wield the authority of the federal government to suppress the rights of free northerners secured by their respective state constitutions.

And it was in this period that freedom of speech began to be considered a “privilege or immunity” of national citizenship, fundamental and guaranteed to every citizen, even those like abolitionists who were otherwise regarded as gadflies by contemporary mores. By the 1850s, the emergent Republican Party “would place the call for free expression at the core of its political agenda.”

Slavery was of course eventually shattered by the bloody crucible of the Civil War. In the aftermath of the war, the nation enacted the Fourteenth Amendment, which expressly prohibited states from denying to any citizen of the United States the privileges or immunities of citizenship. In doing so, the Reconstruction Congress intended to end the oppressive tyranny of the slave states, demonstrated in the antebellum years and continued post-war with “Black Codes” aimed at establishing apartheid in the South. Yet, when the inglorious Redemption set in, the question raised by the enigmatic phraseology of the Fourteenth Amendment remained: what exactly were the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the United States?

A vain and idle enactment

By its explicit terms, the First Amendment prohibits only Congress from abridging freedom of speech and of the press. It does not purport to limit states in any way. As I wrote about in connection with the Second Amendment, however, the U.S. Supreme Court went much further in Barron v. Baltimore (1833), holding that none of the provisions of the Bill of Rights were applicable to the states, even those such as the Fifth Amendment, which did not mention Congress and instead guaranteed the rights of every “person.”

Chief Justice Marshall was likely right in Barron about the applicability of the Bill of Rights to states, as a matter of the Constitution’s original intent. When James Madison initially proposed the Bill of Rights in the First Congress, he included an amendment that would have prohibited states (as opposed to Congress) from violating rights of free speech, religious worship, and to a jury trial in criminal cases.1 But the Senate, whose special function prior to the Seventeenth Amendment was the jealous protection of the prerogatives of the several states, stripped this proto-Fourteenth Amendment from the list of provisions that would eventually become the Bill of Rights.2

It seems like a gobsmacking omission from the modern perspective that the Framers would fail to protect Americans from abuse by states in the Bill of Rights, but from the eighteenth century perspective, it made perfect sense. The Bill was in essence a series of clarifications and glosses on the original Constitution, the central purpose of which after all was to constitute the federal government and establish the scope and limit of its powers. To the extent the Constitution restricted state governments, it mainly did so when necessary to establish corollaries of explicitly granted federal powers.3

States, meanwhile, predated the federal government and were governed by their own, older constitutions, including state bills of rights that robustly protected individual rights.4 The primary concern of the proponents of a federal Bill of Rights was limitation of the power of the federal government, against individuals and against states. To the extent the federal Bill addressed states, then, it was to secure their rights against the national government, as we see in the Tenth Amendment.

But over the course of the first half of the nineteenth century, the popular understanding of the Bill of Rights began to change, from an Anti-Federalist limit on central power to a universal statement of fundamental natural rights, an American Magna Carta. When the Civil War brought the boil of toxic states’ rights ideology to a head, Congress was determined to lance the white supremacist purulence during the ensuing Reconstruction by overruling Barron and applying the Bill of Rights to the states through the Reconstruction Amendments. In particular, section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that

[n]o state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States[.]

So whatever else the “privileges or immunities” secured against the states by the Fourteenth Amendment might include, at a minimum they incorporated the first eight amendments to to the Constitution, as John Bingham, author of the Fourteenth Amendment, explained:

[T]he privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, as contradistinguished from citizens of a State, are chiefly defined in the first eight amendments to the Constitution … These eight articles I have shown never were limitations upon the power of States, until made so by the fourteenth amendment.

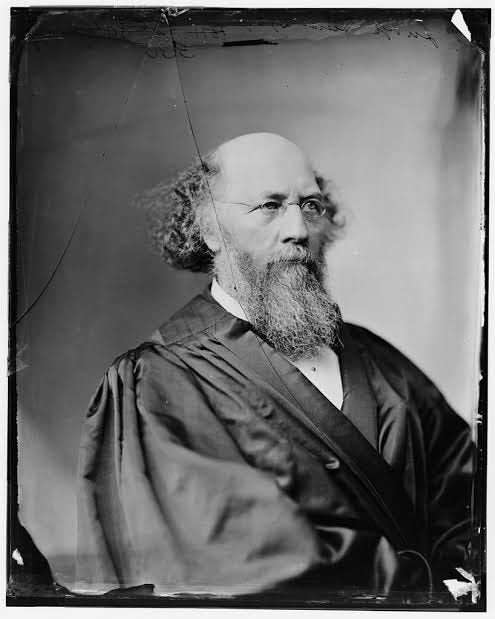

The U.S. Supreme Court did not get the memo however, because as I have written, the court in 1873 denied that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause incorporated the Bill of Rights against states in the Slaughterhouse Cases. Instead the rights set forth in the first eight constitutional amendments were only rights of state citizenship, despite their enumeration in the federal Constitution. The protection of these and other fundamental rights, wrote Justice Miller for the majority, “lay within the constitutional and legislative power of the State, and without that of the Federal government.”

Justice Field, dissenting incredulously, concluded that the Reconstruction had apparently been much ado about nothing. The majority’s crimped interpretation of the Privileges and Immunities Clause turned the Fourteenth Amendment into “a vain and idle enactment, which accomplished nothing and most unnecessarily excited Congress and the people on its passage.”

But the majority’s effort to read the Privileges and Immunities Clause out of the Constitution stuck, and consequently, so did Jim Crow. That provision remains a vestigial appendage to the Fourteenth Amendment to this day, glossed over and totally ignored by lawyers and judges for a century and a half.

The long shadow of Slaughterhouse

Professor Wehan observes that the “reign of Slaughter-House from 1873 until 1925 helped retard the development of free speech jurisprudence by immunizing the actions by state governments abridging freedom of speech from Supreme Court review.” Indeed, the “state of free speech jurisprudence on the eve of the First World War would have looked strikingly familiar to Anglo-American lawyers on the eve of the American Revolution.”

When free speech challenges to state action did reach the high court during the Gilded Era, the justices applied common law principles and upheld speech restrictions on rationales like the prior restraints doctrine. Patterson v. Colorado (1907) was emblematic. Patterson, the publisher of the Denver Rocky Mountain News, was held in contempt of court for publishing material critical of members of the Colorado Supreme Court and challenged to conviction on free speech grounds.

Justice Holmes, writing for the majority, held that, even if the federal constitution did put limits on the power of states to legislate speech (which he did not concede), the “main purpose” of such limits would be to prevent “previous restraints” and not “subsequent punishment” of speech “deemed contrary to the public welfare.”

Nor was truth necessarily a defense, when it came to judicial contempt proceedings at least. Even truthful criticism of the judiciary could after all “tend to obstruct the administration of justice.” Public criticisms of judges produced “bad tendencies” that interfered with the conduct of judicial proceedings.

The court applied the “bad tendency” test again eight years later in Fox v. Washington to uphold the conviction of a militant nudist for violating a Washington statute that prohibited speech encouraging “disrespect for law.” In his anarchist community newsletter, Fox decried the “prudes” who had infiltrated their collective and narced on members to the cops for indecent exposure. He advocated a general boycott until the prudes learned the “brutal mistake” of opposing skinny dipping. Justice Holmes easily concluded that Fox’s advocacy of going about in your birthday suit produced bad tendencies because it encouraged indecent exposure.

During the antebellum years, the slave states had violated the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the United States by criminalizing the “bad tendencies” caused by “disrespect for the law” of slavery. The nation had fought a brutal war for Union and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment precisely to dethrone the tyranny of this state power. But the Supreme Court had learned nothing.

The court instead continued to apply into the modern era an eighteenth century regime of common law free speech restrictions laid down by Blackstone. The Reconstruction Amendments invited the justices to come to grips with their brave new world. But the court hued to the regime set down by the Slaughterhouse Cases. The law’s ancient, shabby rearguard action against the printing press was applied unreflexively and anachronistically to a twentieth century America enchanted by the novelty of the motion picture and unmoored by the horror of industrial war.

Retconning incorporation

I have previously discussed how, at the same time that the court was denying that the privileges and immunities of citizens were a thing, the justices decided that the the Fourteenth Amendment did in fact protect fundamental rights, but under a different part of that provision, the Due Process Clause. During this Lochner era, the court applied economic liberties such as freedom of contract and property rights to protect business interests against the efforts of states to curb the excesses of industrialization.5

In a series of cases in the early 1920s, however, the court began to apply this substantive due process to protect the rights of parents to direct the upbringing of their children against interference by the state. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters, the court struck down an Oregon law in 1925 that made public school attendance mandatory. Children were “not the mere creature[s] of the state” that could be standardized through forced public indoctrination. Due Process protected liberties of the mind as well as those of the pocketbook.

That same year, the court decided Gitlow v. New York, the conviction of a leader of the Revolutionary Communist Party under New York’s criminal anarchy law. Gitlow’s attorney explicitly argued to the court that the Due Process Clause “incorporated” the First Amendment’s Free Speech Clause against the states.

The court had stated categorically only a few years earlier in Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek that “neither the Fourteenth Amendment nor any other provision of the Constitution of the United States imposes on the states any restrictions about ‘freedom of speech.’” But astonishingly in Gitlow, the court shrugged off its statement in Cheek and said that “[w]e may and do assume that freedom of speech and the press which are protected by the First Amendment … are among the fundamental personal rights and ‘liberties’ protected by the Due Process Clause.”

Why did the court suddenly change its mind? Professor White concludes that “[t]his is one of those episodes in American constitutional history when interested persons are reduced to speculation.” Justice Holmes, otherwise a skeptic of economic due process liberties, seemed to imply, however, in his Gitlow concurrence that this was a case of goose and gander. If the court was going to stretch due process all out of shape to protect economic liberties, it could hardly refuse to do so for liberties of conscience and expression.

So even if freedom of speech was not a privilege or immunity of citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment, the Free Speech Clause could still be incorporated against the states through that provision’s Due Process Clause. It was a circuitous and tortured route to enforcement against states. The court had strayed far from the path mapped out by the Reconstruction Congress. But after wandering in the desert for half a century, the justices seemingly reached the promised land.

Or perhaps not. Although the Gitlow court had no problem applying the First Amendment freedom of speech against the New York, the majority also upheld Gitlow’s conviction without trouble. Gitlow’s “Left Wing Manifesto” advocated overthrowing the government by violent means and could be punished under the First Amendment.

Professor White comments that

If Gitlow signaled that the Court was prepared to move into a new world of “incorporated” liberties, thereby subjecting the states to the same restrictions imposed on Congress by bill of rights provisions, it did not signal, in the least, that the Court was henceforth going to adopt a more speech-protective attitude in cases where states sought to restrict speech.

Despite incorporation, we were not out of the free speech woods just yet.

Crucially for this point, the right to a criminal jury trial established by the Sixth Amendment is guaranteed to every person and not limited textually to Congress. There would have been no need for Madison to propose a separate amendment applying criminal jury trials to states if the Sixth Amendment already did so.

In one of those eerie premonitions of history, Madison’s provision to limit state power was his fourteenth proposal.

States are expressly prohibited (art. I, sec. 10, cl. 3) from entering into treaties with foreign nations, for example, because it would undermine the federal government’s enumerated power (art. II, sec. 2, cl. 2) to do so.

Although the enslaved needed not apply, of course.