It’s considered a self-evident truism by many, if not most, Americans that our Constitution enshrines a strict “wall of separation” between church and state. Yet that phrase, “separation of church and state,” appears nowhere in the document. Instead, the First Amendment provides that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Indeed, certain conservatives hotly dispute that such a strict wall separating church and state exists at all in the Constitution. They argue that the Establishment Clause was intended solely to protect the religious establishments of state governments from interference by the federal government. It does not create any individual rights they contend, and was not, in fact logically could not be, incorporated against the states by the Fourteenth Amendment.

In their telling, the efforts of modern federal courts to apply the Establishment Clause against state and local governments, by for example prohibiting official prayer in schools, not only fundamentally misread the clause but perversely upend the First Amendment’s original purpose by turning it against the very states it was designed to protect. Insulating from federal interference the discretion of such local authorities to officially establish religion as they saw fit was precisely the reason for the Establishment Clause. The Heritage Foundation, for example, decries how

[a] barrier originally designed, as a matter of federalism, to separate the national and state governments, and thereby to preserve state jurisdiction in matters pertaining to religion, was transformed into an instrument of the federal judiciary to invalidate policies and programs of state and local authorities.

Have we totally misunderstood the Establishment Clause? And if so, where did we get this supposedly erroneous idea of a wall of separation of church and state, if not from the Constitution itself?

The rise and fall of the house of Lemon

Like much of the Bill of Rights, the Establishment Clause lay mostly dormant until the mid-twentieth century. In 1947, however, the U.S. Supreme Court incorporated the Establishment Clause against the states in a case called Everson v. Board of Education. There, the court upheld, on a 5-4 vote, a New Jersey statute that authorized school districts to reimburse parents for costs of busing their children to private schools, including religious schools.

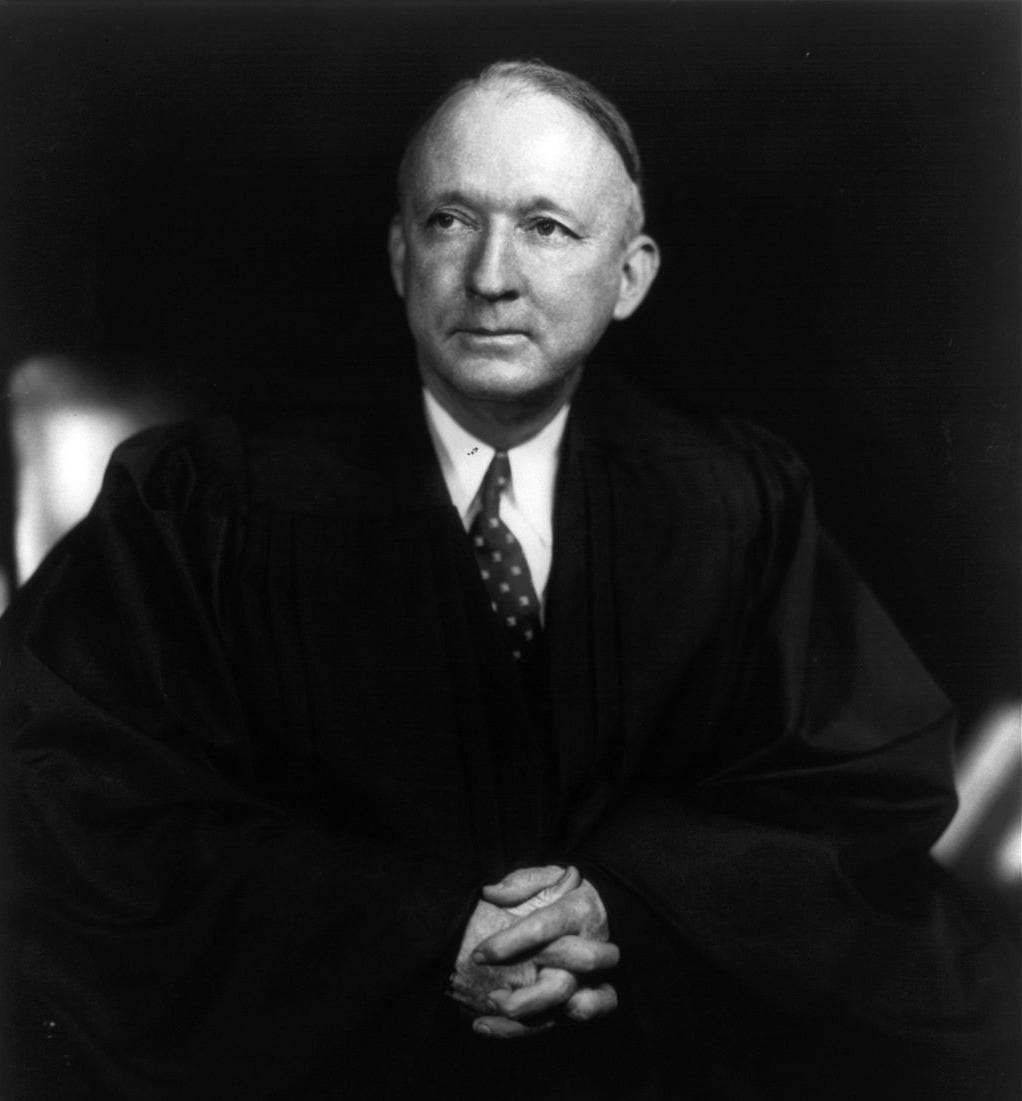

Justice Black invoked the “wall of separation” between church and state in his majority opinion, but nevertheless reasoned that the reimbursements for religious school attendance did not violate the Establishment Clause because they were available to attendees of secular and religious schools on an equal basis. The First Amendment “requires the state to be neutral in its relations with groups of religious believers and non-believers.” Justice Jackson, in dissent, disagreed because “to render tax aid to its Church school is indistinguishable . . . from rendering the same aid to the Church itself.”

Fifteen years later, the court struck down official prayer in public schools in Engel v. Vitale. In that case, teachers of the Union Free School District in New Hyde Park, N.Y. led students in nondenominational Christian prayer recommended by the New York Board of Regents. Participation was not mandatory and students could obtain an exemption with a written parental request.

Writing for a six justice majority, Justice Black relied on the history of official religious oppression in England and the American colonies to conclude that “the First Amendment was added to the Constitution to stand as a guarantee that neither the power nor the prestige of the Federal Government would be used to control, support or influence the kinds of prayer the American people can say.” But Justice Stewart thought that Black had “misapplied a great constitutional principle” because the nation’s history was packed full of officially sponsored prayers, days of thanksgiving, invocations of God, and other similar nondenominational religious recognitions.

In 1972 the court synthesized the existing Establishment Clause jurisprudence into a three part test in Lemon v. Kurtzman. According to the court, to pass muster under the Establishment Clause, the government’s action must

have a secular purpose,

not have a primary effect of promoting or inhibiting religion, and

not result in excessive government entanglement with religion.

States had provided direct taxpayer funded payments to support religious private schools. The court held in Lemon that although the states may have had a secular purpose (promoting education), the payments resulted in excessive entanglement with religion because state governments would be in a position to monitor and dictate the operations of religious institutions dependent on public funds.

The Lemon test turned out to be nebulous and difficult for courts to apply consistently. The case was criticized in many quarters and various addenda and alternatives were proposed, such as Justice O’Connor’s endorsement test and Justice Kennedy’s coercion test. Although the court tinkered with the individual prongs of the test over the years, however, it left the controversial precedent nominally in place until 2022.

By then, the Lemon test was thoroughly moribund, a “ghoul,” according to Justice Scalia, that “repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried, [in order to] stalk[] our Establishment Clause jurisprudence.” The court finally banished Lemon back to its crypt for good in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District.

Kennedy was a high school football coach in Washington State who adopted the practice of standing on the 50-yard line to pray after games. Soon players from both teams began to join him and he started leading group prayers for the assembled student athletes on the field. When Kennedy led these public prayers he was technically still on the clock as a school employee but the immediate post-game period was a sort of officially-sanctioned downtime when teachers and coaches could check their phones, chat with spectators, and engage in other similar personal activities.

When Kennedy’s activities came to the attention of school officials, the school district requested that he cease his post-game prayers. Although he agreed to stop leading the students in out-loud prayers, he insisted on continuing to pray silently at the 50 yard line. As a result, the school district terminated his employment.

Justice Gorsuch, writing for the six Justice conservative majority, held that the Bremerton School District had violated Kennedy’s rights under the Free Exercise Clause. Because school employees were allowed to engage in secular personal activities after games, like making private phone calls and chatting with friends, the school district could not prohibit an employee’s personal religious activities during that same time.

The school district responded that it had to single out Kennedy’s religious conduct under the Establishment Clause. Citing Lemon and its progeny, the district argued that a “reasonable observer” who saw Kennedy, an on-duty school employee, publicly praying on the field immediately after the conclusion of a school event would conclude that the district endorsed his religious activities.

Gorsuch rejected Lemon altogether as “abstract and ahistorical.” Rather, the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by “reference to historical practices and understandings.” What historical practices were relevant analogues to Kennedy’s conduct? Gorsuch did not say. He did seem to find it important that Bremerton students were not explicitly forced or pressured into joining their coach’s post-game prayer. Coercion, then at least, is a relevant consideration in identifying an Establishment Clause violation in the eyes of the court’s conservative majority. Yet, Justice Gorsuch did not ground even that factor in any historical context or give a single law, practice, or event from history as a basis.

Justice Sotomayor, in dissent, noted how the majority had “reserve[d] any meaningful explanation of its history-and-tradition test for another day, content for now to disguise it as established law and move on.” Indeed, if judges and lawyers, aided by voluminous amicus briefs of eminent historians, struggled to apply centuries old standards to modern circumstances, how could harried school administrators possibly be expected to do so?

The crumbling wall

Whatever the defects of Lemon and its progeny, those cases were fundamentally concerned with maintaining a strict wall of separation between church and state. Under Lemon, governments were required to scrupulously avoid entangling themselves with religious institutions and even the appearance of an official endorsement of religion was sufficient to sustain an Establishment Clause violation.

Kennedy was the final nail in the coffin of the Lemon test, the culmination of the Roberts court’s years long project to erode the Establishment Clause down to a nub while elevating the Free Exercise Clause above other concerns. Eric Segall argues that we have reached “the point that a state's good faith efforts to comply with the establishment clause now violate the free exercise clause.” Justice Sotomayor made a similar observation in her Kennedy dissent. The court, she wrote, had

elevate[d] one individual’s interest in personal religious exercise, in the exact time and place of that individual’s choosing, over society’s interest in protecting the separation between church and state, eroding the protections for religious liberty for all.

But is this emasculation of the Establishment Clause really dictated by the Constitution’s historical understanding? What Founding era experience sheds light on the original meaning of the prohibition on laws respecting establishments of religion? If a strict wall of separation is not the right metaphor, what is?